WHITE WINGS

2020 — 2023

Like many authors, during the pandemic I found myself in isolation alone with my feelings. And I realised that if I lost control of them, they would literally eat me up from the inside. This project was my reaction to the situation in which I found myself and the same time — my way of manage it.

The butterfly is a universal symbol of the immortality of the soul, feelings and emotions. But if we take a closer look at it, we will see furry monster with wings covered by scales. We eat ourselves with emotions, first losing a piece of wings, then — the head, and so on, until there’s only a ghostly imprint left of the feelings.

Lupina et Divina

Irina Chmyreva, PhD, AICA member, art-director of PhotoVisa, the international festival of photography

Photographer Andrey Akimov began his letter by mentioning a song, a hit from the 1970s, “White Wings”. Listening to it, you can experience a dissonance: a light and pleasant melody, and a tragic text about an irretrievable love that has gone, an upbeat rhythm, and the breaking voice of the song’s first performer. The album was recorded at a time when people believed in the concrete masses of brutalism and girls wore short dresses and high hairdos. In spring the heart clenched at the sight of the white petals of the blossoming trees snowing, and in the face of this ordinary and eternal feeling of nostalgia for the change of season, all fashion faded, as if the stage lights were turned off and only a spotlight illuminated what mattered most: the falling petals, telling the passing moments of our own lives.

Like white pearls telling of inevitability, the weightless grains of butterfly wing scales leave traces on the black velvet of the artist’s photographs.

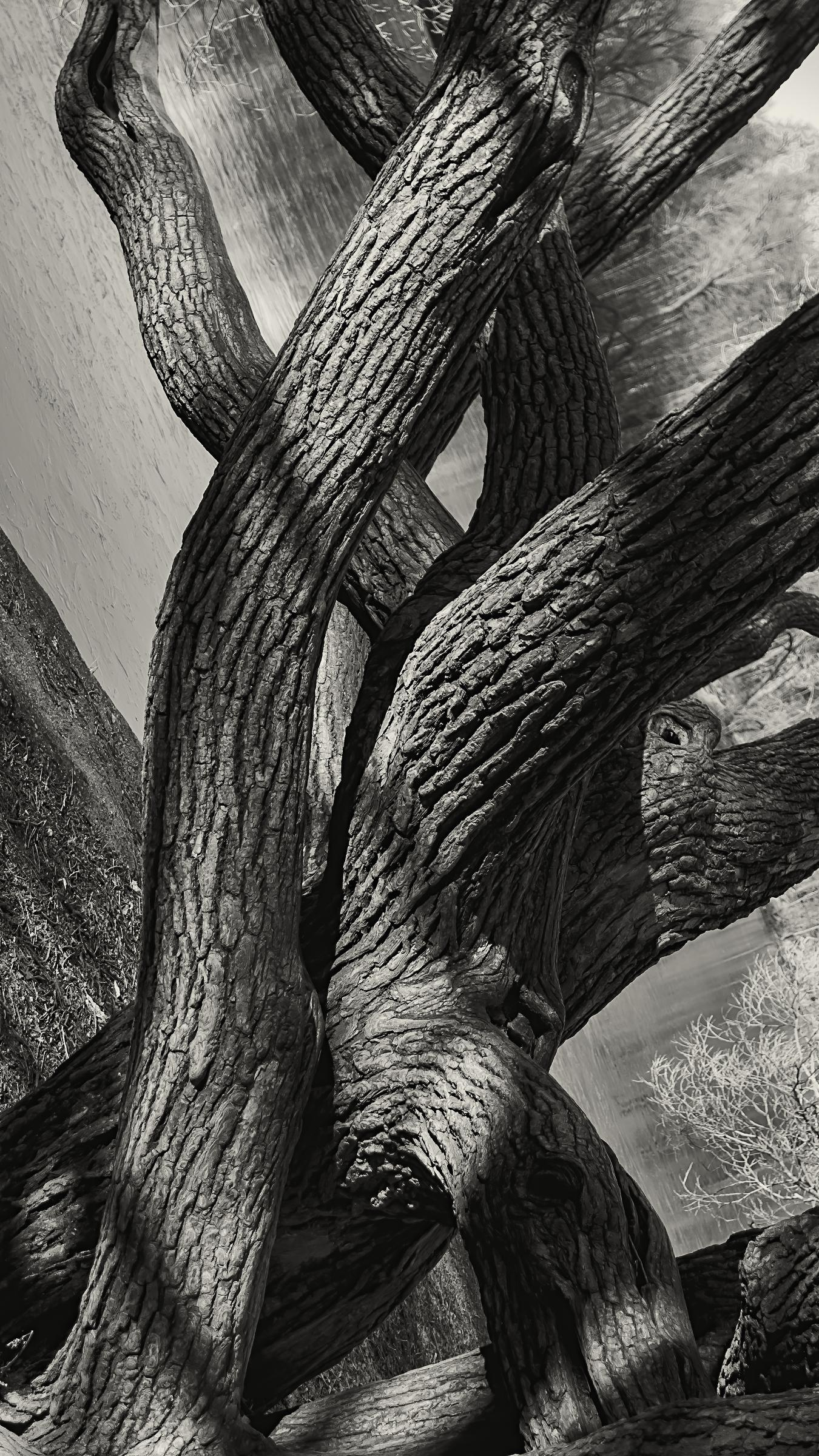

Akimov began White Wings

after his work with fossils in the series The Fossil, which featured baroque

curls of shells and layered ripples of stones — the art of the Creator —

millions of years before the advent of the baroque era. This series, like the

previous one, relied on the oversizing of objects. Fossil brought us closer to

the idea of the abolition of time, or rather to the suppression of its

linearity: we found ourselves inside a spiral, where past and present were

juxtaposed like the annual rings of a tree growing simultaneously in all directions,

upwards, outwards and rooted in the black depths.

During the quarantine a new

series began, when the speculative cell of the mathematical hypothesis of the

annulment of time, in a single instant, was realized and made lasting. All of

us, while locked up, had a timeless existential experience with our own

memories. The paradox of the pandemic had no end. The new reality consisted of

a life without the marks of a path, it was lost, compressed to the size of a

cage-room.

Literally, we all went

through the experience of a life imprisonment. At the time, Andrey saw in the

lepidopteran specimens crumbled by dilapidation, a metaphor for sensual

memories: when approached, in a moment of exaltation, they became intimidating,

capable of consuming, burning with the power of vital feelings, but as they

receded into the past, they became cold, dead, crumbling into a fine white

powder.

In 2020, the artist couldn’t know, only anticipate, how time compresses and new meanings are imposed on us: after the pandemic came the war. The white nets, the white fibers of particles of the living body shaken on the dark velvet began to resemble bandages. They wouldn’t have served to heal the wounds, but to cover, to hide from the observer the horrors of open flesh that screams in pain on the threshold of death, the darkness opens. It expands, filling with its omnipresence all that is accessible to it, it has no dimensions, no three spaces, no fourth time. In Akimov’s photographs of butterflies, the black background becomes a terrifying character, which only a fine net, weightless particles of shredded scales, prevents contact with the viewer’s world.

In his photographs, if we move away from his own allusions, although important as historical evidence of the moment of creation, the poetry of Osip Mandelstam resonates: it was he, the first Russian poet, who gave his name to the current century: the wolf-age hound. The age in which comes that which is more frightening than fear: no longer the wolves come in the night, but those who are stronger, more powerful, those through whom the wildest savagery emerges in its endless darkness. The little poet with his words, like scattered fragments of stardust, wounded himself with blood, sprinkles the blackness of hopelessness, creating a barrier of light between us and it. Akimov has his own weapon of light: tiny scales of butterflies’ wings. Among the winged heroines, who after their death also gave up their bodies for a good cause, there are those whom the ancients called wolfish [lupina], there are the goddesses [divina], there are the virgins of ancient Parnassus and Olympus: Persephone, Hecate, Leto, Phoebe, — their names, kept by entomologists as incantations, the photographer carries them into the titles of the works.

In the minimalist black (what is more important for us in these images, the background or the barrier between it and us?) of Andrey Akimov’s photographs the time reveals itself: from the darkness of cruelty, which for centuries was considered brutal (the human species has surpassed all in savagery and senselessness of murder), to the divine.

For available prints and additional images, please contact us